Sensors play a key role when it comes to monitoring flammable gases and vapours. Environment, response time and temperature range are just some of the things to consider when deciding which technology is best.

In this blog, we’re highlighting the differences between pellistor (catalytic) sensors and infrared (IR) sensors, why there are pros and cons to both technologies, and how to know which is best to suit different environments.

Pellistor sensor

A pellistor gas sensor is a device used to detect combustible gases or vapours that fall within the explosive range to warn of rising gas levels. The sensor is a coil of platinum wire with a catalyst inserted inside to form a small active bead which lowers the temperature at which gas ignites around it. When a combustible gas is present the temperature and resistance of the bead increases in relation to the resistance of the inert reference bead. The difference in resistance can be measured, allowing measurement of gas present. Because of the catalysts and beads, a pellistor sensor is also known as a catalytic or catalytic bead sensor.

Originally created in the 1960’s by British scientist and inventor, Alan Baker, pellistor sensors were initially designed as a solution to the long-running flame safety lamp and canary techniques. More recently, the devices are used in industrial and underground applications such as mines or tunnelling, oil refineries and oil rigs.

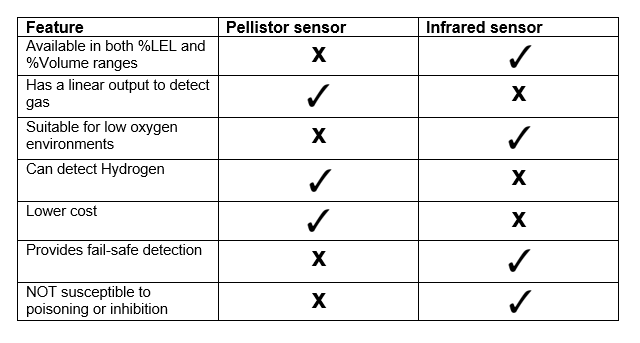

Pellistor sensors are relatively lower in cost due to differences in the level of technology in comparison to IR sensors, however they may be required to be replaced more frequently.

With a linear output corresponding to the gas concentration, correction factors can be used to calculate the approximate response of pellistors to other flammable gases, which can make pellistors a good choice when there are multiple flammable vapours present.

Not only this but pellistors within fixed detectors with mV bridge outputs such as the Xgard type 3 are highly suited to areas that are hard to reach as calibration adjustments can take place at the local control panel.

On the other hand, pellistors struggle in environments where there is low or little oxygen, as the combustion process by which they work, requires oxygen. For this reason, confined space instruments which contain catalytic pellistor type LEL sensors often include a sensor for measuring oxygen.

In environments where compounds contain silicon, lead, sulphur and phosphates the sensor is susceptible to poisoning (irreversible loss of sensitivity) or inhibition (reversible loss of sensitivity), which can be a hazard to people in the workplace.

If exposed to high gas concentrations, pellistor sensors can be damaged. In such situations, pellistors do not ‘fail safe’, meaning no notification is given when an instrument fault is detected. Any fault can only be identified through bump testing prior to each use to ensure that performance is not being degraded.

IR sensor

Infrared sensor technology is based on the principle that Infrared (IR) light of a particular wavelength will be absorbed by the target gas. Typically there are two emitters within a sensor generating beams of IR light: a measurement beam with a wavelength that will be absorbed by the target gas, and a reference beam which will not be absorbed. Each beam is of equal intensity and is deflected by a mirror inside the sensor onto a photo-receiver. The resulting difference in intensity, between the reference and measurement beam, in the presence of the target gas is used to measure the concentration of gas present.

In many cases, infrared (IR) sensor technology can have a number of advantages over pellistors or be more reliable in areas where pellistor-based sensor performance can be impaired- including low oxygen and inert environments. Just the beam of infrared interacts with the surrounding gas molecules, giving the sensor the advantage of not facing the threat of poisoning or inhibition.

IR technology provides fail-safe testing. This means that if the infrared beam was to fail, the user would be notified of this fault.

An example of one of our IR based detectors is the Crowcon Gas-Pro IR, ideal for the oil and gas industry, with the availability to detect methane, pentane or propane in potentially explosive, low oxygen environments where pellistor sensors may struggle. We also use a dual range %LEL and %Volume sensor in our Gas-Pro TK, which is suitable for measuring and switching between both measurements so it’s always safely operating to the correct parameter.

However, IR sensors aren’t all perfect as they only have a linear output to target gas; the response of an IR sensor to other flammable vapours then the target gas will be non-linear.

Like pellistors are susceptible to poisoning, IR sensors are susceptible to severe mechanical and thermal shock and also strongly affected by gross pressure changes. Additionally, infrared sensors cannot be used to detect Hydrogen gas, therefore we suggest using pellistors or electromechanical sensors in this circumstance.

The prime objective for safety is to select the best detection technology to minimise hazards in the workplace. We hope that by clearly identifying the differences between these two sensors we can raise awareness on how various industrial and hazardous environments can remain safe.

For further guidance on pellistor and IR sensors, you can download our whitepaper which includes illustrations and diagrams to help determine the best technology for your application.

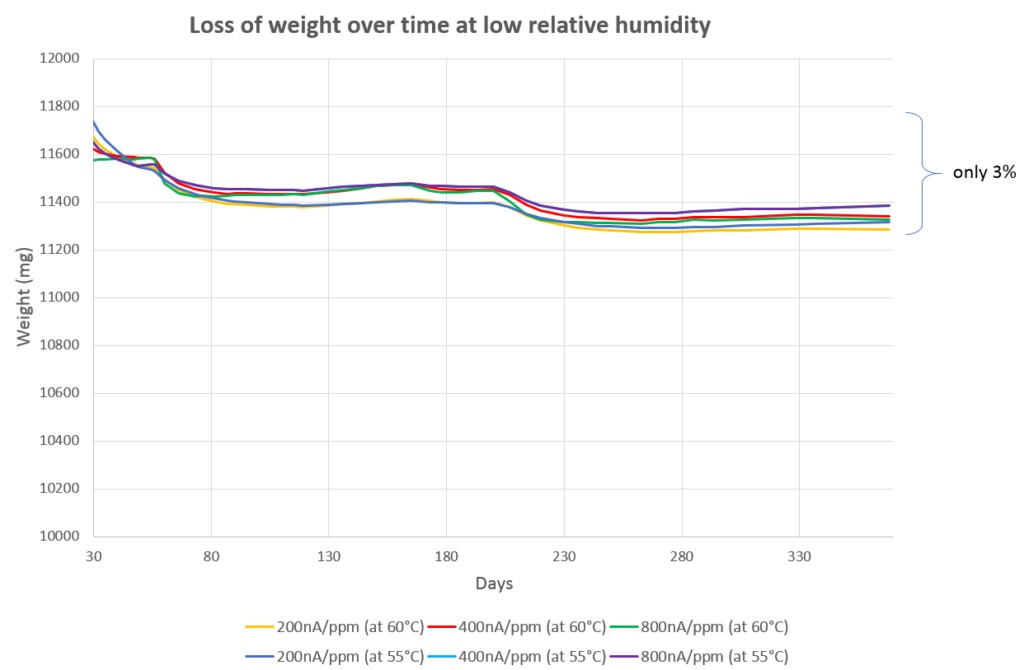

In traditional H2S sensors, detection is based on electrochemical technology, where electrodes are used to detect changes induced in an electrolyte by the presence of the target gas. However, high temperatures combined with low humidity causes the electrolyte to dry out, impairing sensor performance so that the sensor has to be replaced regularly; meaning high replacement costs, time and efforts.

In traditional H2S sensors, detection is based on electrochemical technology, where electrodes are used to detect changes induced in an electrolyte by the presence of the target gas. However, high temperatures combined with low humidity causes the electrolyte to dry out, impairing sensor performance so that the sensor has to be replaced regularly; meaning high replacement costs, time and efforts.